There’s something profoundly human about pausing to notice a flower. The same can be said about standing in front of a painting, taking it in slowly, letting the details work on you. It’s no surprise then that some of the world’s most iconic works of art are obsessed with flowers in all their fleeting, extravagant, stubborn beauty.

In this piece, we’ll explore a few of the most famous floral paintings in art history—from Van Gogh’s Sunflowers to Monet’s Water Lilies—and the real flowers that inspired them. And if you’re the sort of person who keeps a vase of fresh stems by your desk, maybe you’ll see them a little differently next time.

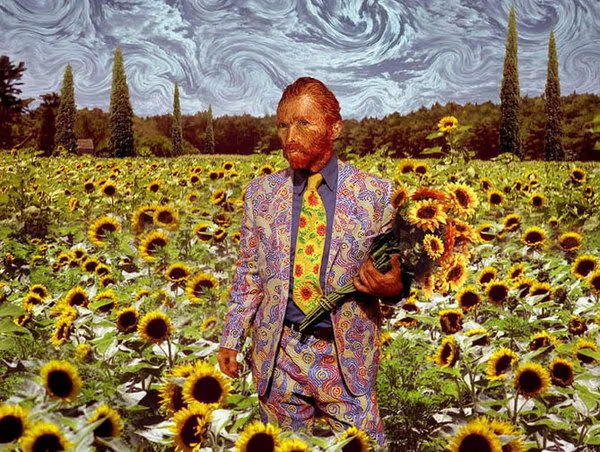

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers: The Bold, the Broken, the Brilliant

Vincent van Gogh didn’t just paint flowers. He inhabited them. His series of Sunflowers is famous not because they’re pretty (though they are, in their own unruly way) but because they’re alive with feeling.

Painted in Arles in the late 1880s, these portraits of sunflowers were meant to decorate the room of his friend Paul Gauguin. But there’s nothing purely decorative about them. The yellows are fierce, layered in thick impasto, the brushwork urgent. Van Gogh himself said the flowers were “mine in a way,” claiming them as an extension of his own restlessness and search for hope.

In real life, sunflowers (Helianthus annuus) are symbols of warmth and loyalty. They turn their faces to the sun—a kind of natural optimism Van Gogh both admired and perhaps envied. He famously wrote to his brother Theo about finding “a sunflower to lean on.”

When you see a bunch of sunflowers today, even in a florist’s window, it’s hard not to think of Van Gogh’s tortured hope: the promise that beauty can be both bright and battered, luminous even in decay.

Monet’s Water Lilies: Light, Reflection, and the Illusion of Stillness

Claude Monet’s Water Lilies are almost a synonym for impressionism itself. These paintings weren’t just inspired by flowers—they were part of Monet’s lived environment. He cultivated his famous water garden at Giverny with obsessive care, designing it specifically as a subject for his art.

He didn’t just glance at the pond; he studied it relentlessly, tracking the changing light and reflections. The water lilies (Nymphaea) themselves become a kind of meditation. In the paintings, they float between worlds—between water and sky, solid form and liquid colour.

The real flowers are hardy aquatics that root in mud and reach for the surface. Their blossoms open and close with the sun. For Monet, they were perfect metaphors for transience, for the way beauty drifts in and out of view.

Seeing water lilies in a garden today can still conjure that sense of contemplative calm. They remind us of patience, of paying attention to what changes even as it seems to stay the same.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Calla Lilies: Intimacy in Bloom

Crossing continents, Georgia O’Keeffe brought an entirely different approach to flowers. Her close-up paintings of calla lilies, poppies, and irises turned petals into vast, sensual landscapes.

Her Calla Lily series is striking for its focus and scale. She zooms in until the flower is all you see—no background noise, no distractions. The undulating forms suggest something bodily, alive, a hint of eroticism that O’Keeffe always claimed was simply about seeing clearly.

Calla lilies (Zantedeschia) in the real world are striking but understated. Elegant, sculptural, almost architectural. They’re often used in weddings and funerals alike—marking beginnings and endings with quiet drama.

O’Keeffe’s work asks us to look harder, to see flowers not as accessories but as powerful subjects in their own right.

Jan van Huysum’s Flower Still Lifes: Abundance and Impermanence

Travel back to the Dutch Golden Age, and you’ll find a very different floral tradition. Artists like Jan van Huysum painted riotous, meticulously detailed still lifes overflowing with tulips, roses, peonies, poppies—even flowers that didn’t bloom at the same time in real life.

These compositions weren’t just showcases of skill. They were meditations on abundance and impermanence. Look closely and you’ll see fallen petals, curling leaves, sometimes even insects feasting on decay.

The real flowers in these paintings were luxury items. Tulips in particular were a kind of status symbol (remember the infamous “Tulip Mania”?). Today, they’re far more accessible, but they still carry that sense of artful decadence.

Arranging a mixed bouquet at home can feel like a small tribute to these old masters—embracing imperfection, celebrating fleeting beauty.

Flowers as Art, Flowers in Life

What links all these works isn’t just the flowers themselves, but the human impulse to make something lasting out of something transient.

A painting freezes a moment when the light hits just so, when a petal is at its brightest. In real life, those moments slip through our fingers, but we keep buying flowers anyway. We keep arranging them, gifting them, pausing to admire them.

Maybe that’s the point. Art can make us notice the real thing more carefully. Van Gogh’s urgent sunflowers, Monet’s luminous water lilies, O’Keeffe’s intimate callas—they don’t replace the flowers in the world. They send us back to them, better equipped to see.

So next time you pick up a bunch from your local florist, take an extra moment. Think about the artists who were just as captivated. Think about how even the most familiar bloom can hold whole worlds, if you’re willing to really look.